“Your grandfather studied in the Dār al-Muʿallimīn madrasa when he was in Uzbekistan.” These were my mother’s words on the final voice note she sent me, wishing me a safe trip to Uzbekistan. Growing up, my mother would tell me stories about my maternal grandfather: how he secretly taught Islam to my mother and her siblings under the Soviet Regime, how his family was specifically persecuted for being Sayyid, how his father sent him to study Islam in Samarkand, how he fought as a Russian soldier in World War II, among other stories. Traveling to Uzbekistan was not just a tourism trip for me—it was a journey of the heart. This land holds so much that is dear to me. Here lies the leader of the hadith scholars, Imam al-Bukhari, may Allah have mercy on him. The graves of leading Hanafi jurists and the revered Imam Maturidi are here. The old Islamic madrasas and masajid with their serene courtyards are here. The stunning, blue-tiled buildings are here. The authentic sambusa and mantu are here. The traditional yaktak and chapans are here. The Persian architecture and language are here. My ultimate mission of conveying Islam is here.

Tashkent

May 25, 2023 / Dhul Qa’da 17 1445

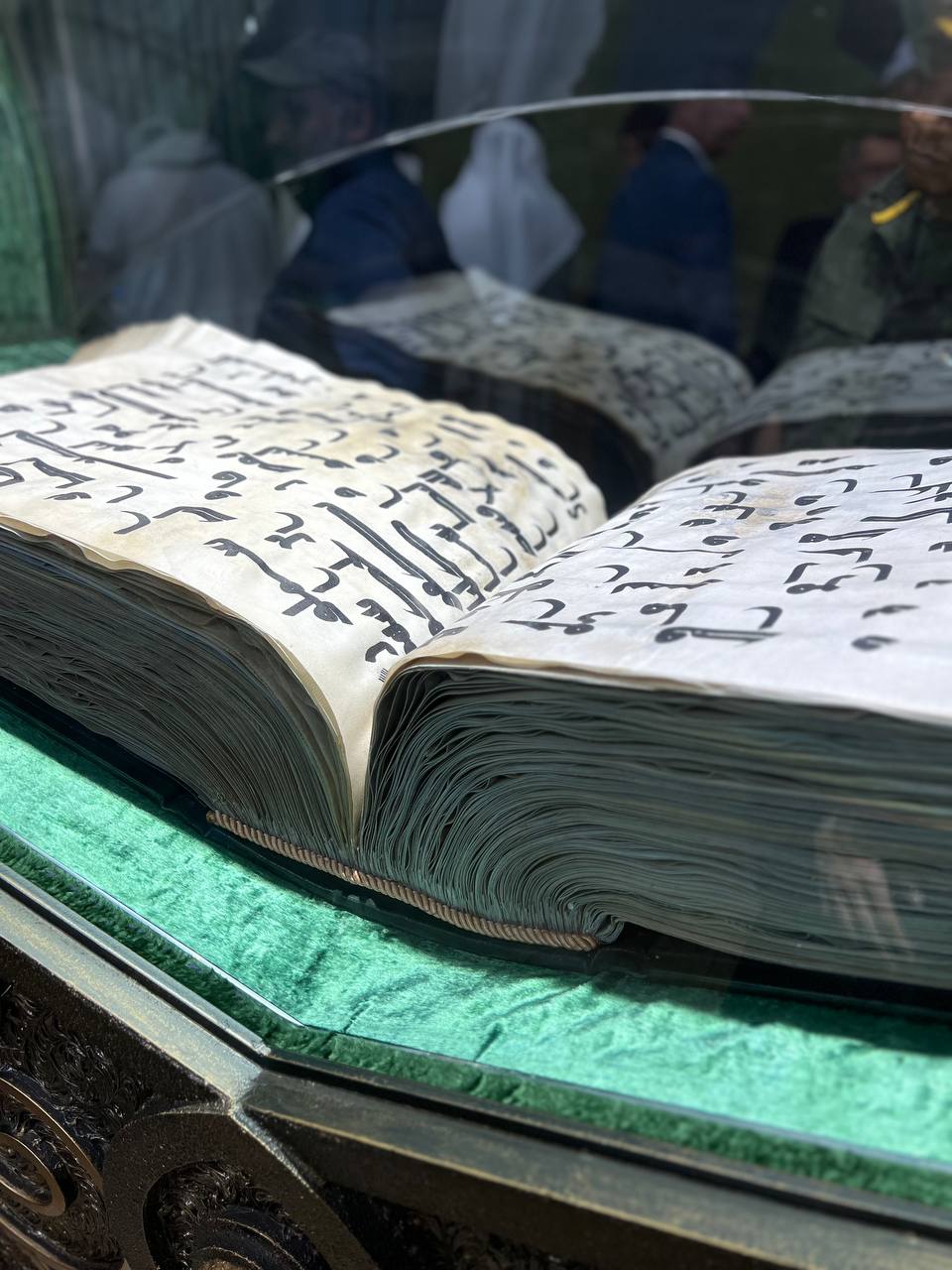

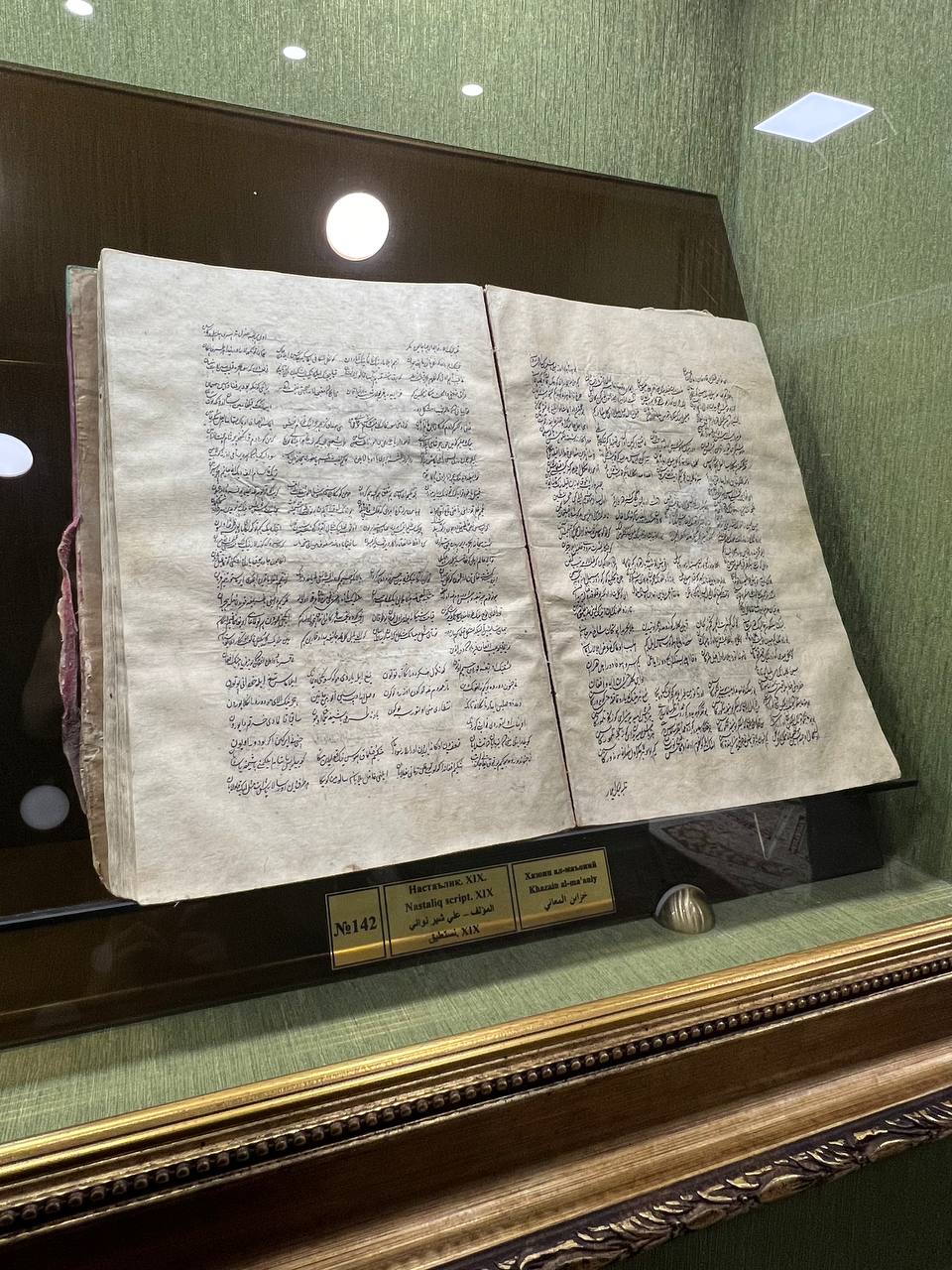

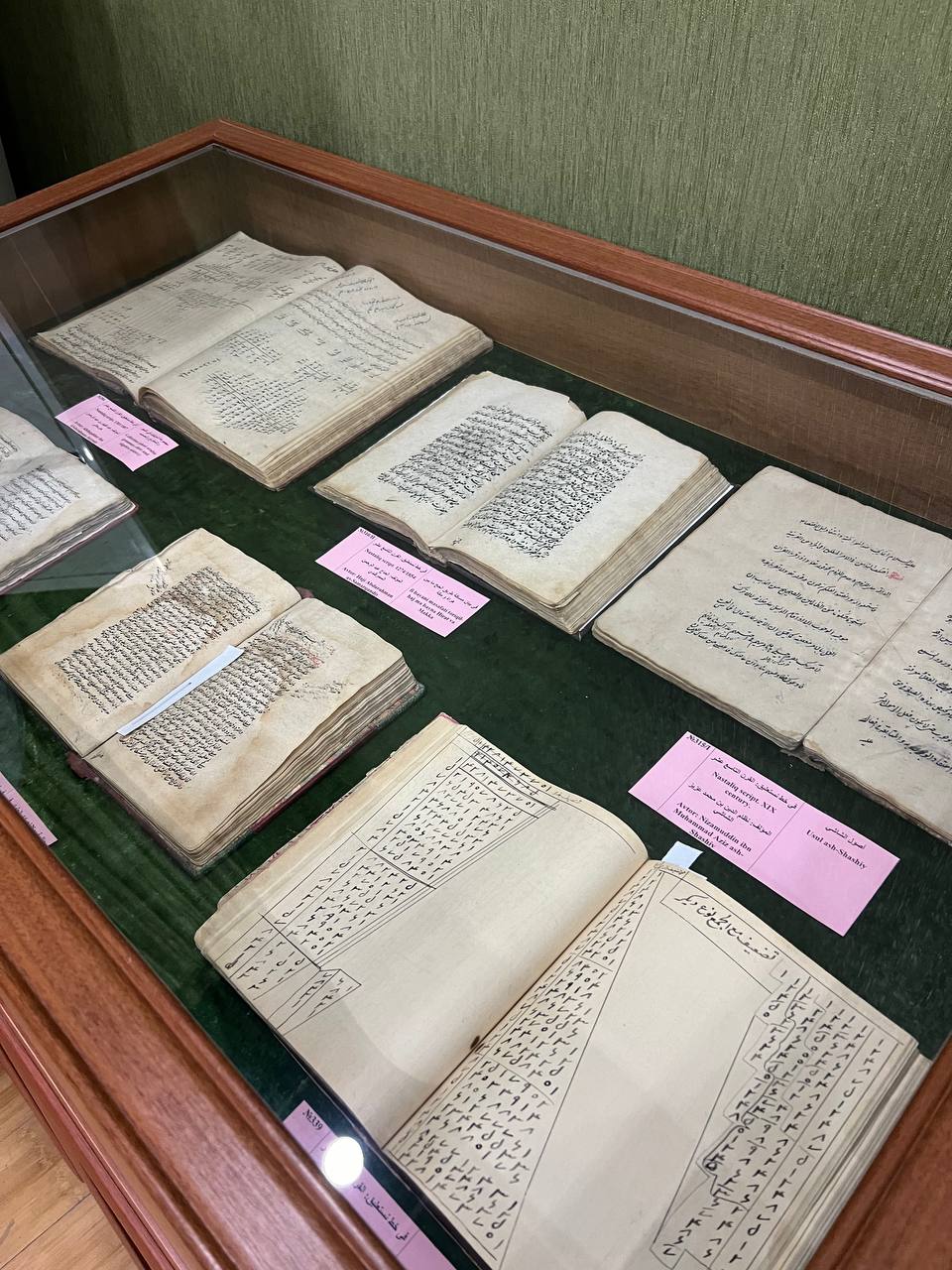

International Islamic Academy

The first day started immediately after a long flight from the UK through Turkey. Nostalgia washed over me as I saw the streets of Tashkent adorned with flower-patterned grass fields and tree trunks painted white halfway up. We waited for everyone to gather outside the airport before boarding the coach and beginning our trip. Our first stop was the O’zbekiston Xalqaro Islom Akademiyasi (The International Islamic Academy of Uzbekistan), a higher educational institution founded in 2018. This institution has several departments, one of the main ones being the Manuscript Depository. During the Soviet Union, religion was persecuted, so out of fear, people would hide these manuscripts by burying them and storing them in the walls of their houses. Since gaining independence in 1991, the government been working on gathering these manuscripts into their museums. The Department researches, publishes, catalogues, and reintroduces unique manuscripts. At present, the repository has about 500 manuscripts, almost 1500 lithographic editions, and over 10,000 modern books. The department carefully preserves a replica of the Qurʾān copy of ʿUthmān produced by an Uzbeki calligraphist (different to the one in the Mo’yi Moborak masjid), as well as manuscripts containing historical information on Sufism, Mantiq, Balagha, mathematics, astronomy, geometry, medicine, and natural sciences.

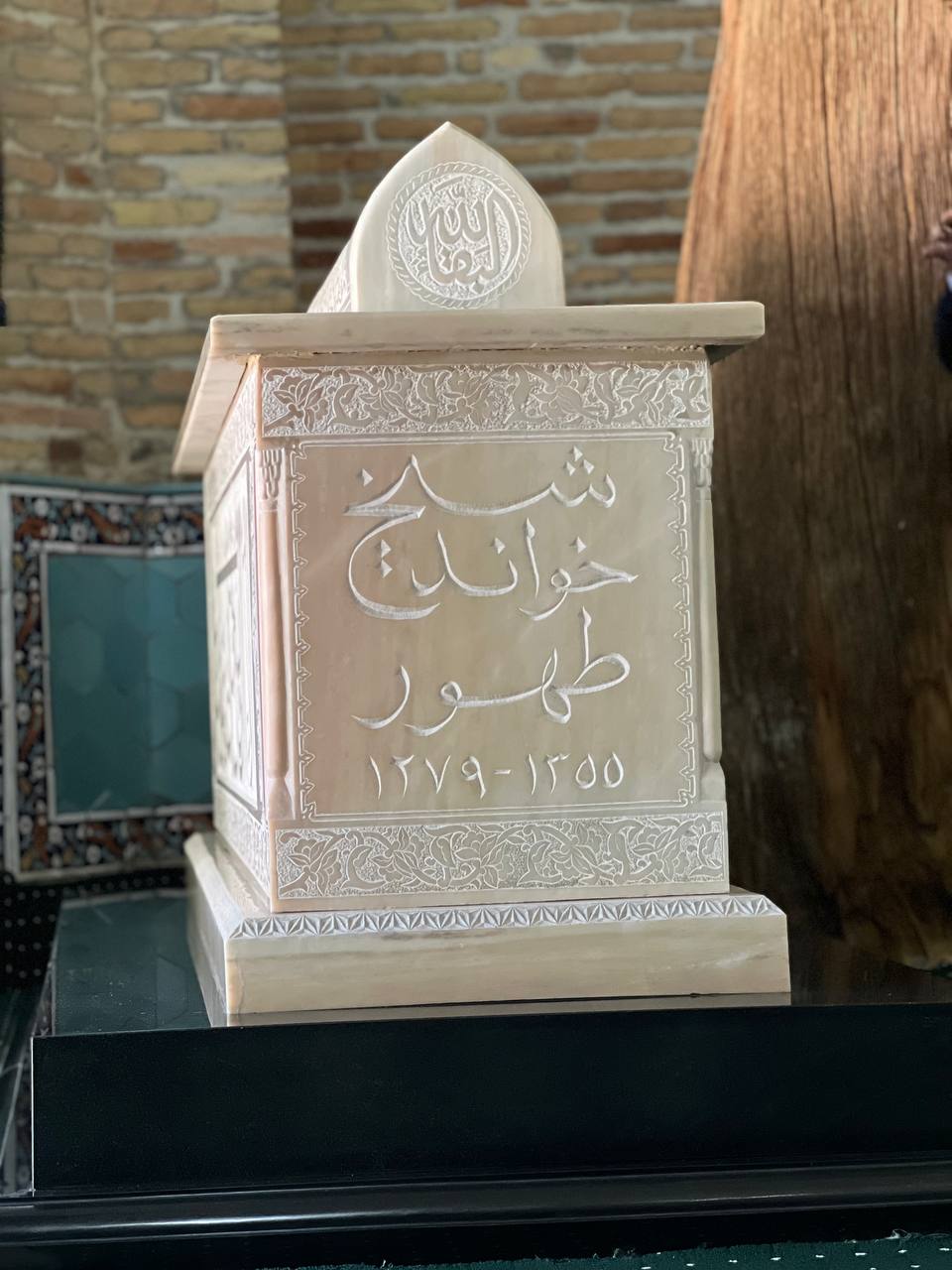

Sheikh Hovendi at-Tahur Complex

By noon, we visited the Sheikh Hovendi at-Tahur Complex. It centres around the Mausoleum of Shaykh Khawand at-Tahur. The complex is located in the heart of Tashkent, near the streets of Alisher Navoi, Shaykhantohur, and Abdulla Kadiri. The mausoleum was built in the 14th century and stands as a tribute to Shaykh Khawand at-Tahur, who belonged to the Quraish tribe. His father, Shaykh Umar, traced his lineage back to the seventeenth generation of the second righteous caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab. The men in Shaykh Umar’s family held the honourable title of Khwaja. Shaykh Khawand at-Tahur played a significant role in spreading Islam a Sufi who played a significant role in spreading Islam in the region.

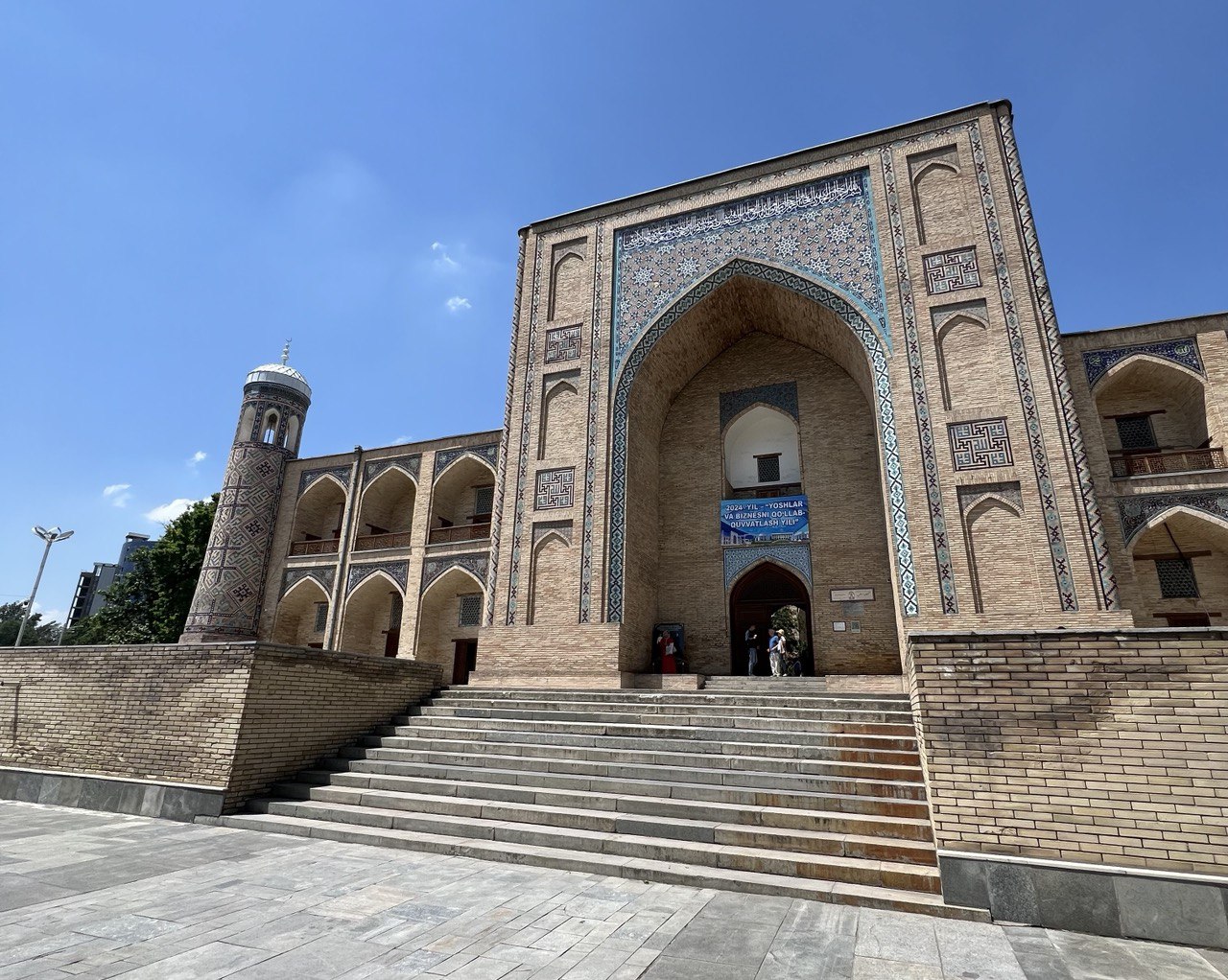

Ko’kaldosh Madrasa

Next, we visited the Ko’kaldosh Madrasa, built around 1570 by the Shaybanid ruler Dervish Sultan. Inside its walls, the rooms around the inner courtyard housed students. This place touched me deeply. Growing up studying Islam in Canada at a dar al-‘ulum, I often felt like I had to blend in with my peers from the Subcontinent. I avoided talking about my own culture and tried to fit in. As I grew older and learned more about my roots, I finally felt confident and content. But I still felt a void—longing for a connection to my own people who studied the Din. This is why the Ko’kaldosh Madrasa was so moving for me. For the first time, I saw my own people studying Islam freely, embracing their own unique attire and culture. Young men walked in and out of their chambers, wearing traditional ‘yaktak‘ coats and distinctive square hats with white patterns. Their curriculum was an adaptation of the well-known ‘Nizami curriculum,’ similar to what’s studied in the dar al-ulums of the Subcontinent, South Africa, and parts of the Western World. A few classrooms were reserved for women to attend weekly classes, though the madrasa officially catered to boys.

Chorsu Bazar and Reactions to My Modest Attire

We then headed to the Chorsu Bazar, which was only a few meters away from the academy. While I normally find nothing interesting about shopping malls or bazars in general, this bazar filled me with so much nostalgia and joy. The smell of traditional meat-and-onion-filled ‘Sambusa‘, the fried ‘Pirashki‘ and sausage rolls, the sweet aroma of golden sugar buns and simits, the endless stalls of traditional ‘ikat‘ and ‘adras‘ patterns with sparkly square scarves brought back so many memories.

Though I felt at home, I got a lot of stares for looking so ‘Arab.’ I wasn’t offended though; the locals weren’t used to seeing someone in a full black abaya and niqāb. In these lands, women have their own distinct modest attire. Had I lived here, I believe it would be appropriate to dress according to their customs of modesty. The ban on hijab in Uzbekistan was only lifted in 2021, and it is still banned in Tajikistan. So, it’s understandable that my black Saudi-style outfit seemed unusual to them.

While this attire is common in many Western countries as the Muslim woman’s attire, it isn’t the only one. Unfortunately, some people need to visit other Muslim countries to realise that the black-abaya-niqāb style most likely originates from the Arab world. Although it is perfectly modest and considered ideal by many, women in other lands are not bound to the same attire.

Hazrati Imom Complex

We then headed to the Hazrati Imom Complex. The complex consists of the Moʻyi Muborak Madrasa, the Qaffol Shoshi Mausoleum, the Baroqxon Madrasa, the Hazrati Imam Masjid, the Tillashayx Masjid, and the Imam al-Bukhari Islamic Institute. The Hazrati Imam complex was built around the tomb of Imām Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī Ismoil ash-Qaffol Shoshi, which is the first building we entered. There were around 20 of us in total, only four of us women, in the company of one of my teachers in hadith, Shaykh Mohammed Daniel (may Allah preserve him). Prior to the trip, we had divided a number of relevant works among three readers, me being one of them, which we were going to read short portions of in their respective locations. Here, we sat by the grave of Imam Qaffal ash-Shashi. After my husband read a part of the ‘Shamāʾil an-Nubuwwa’, it was my turn to read the beginning of ‘Maḥāsin ash-Sharīʿa. I was sitting at the edge of the wall, barely within the view of everyone else. When I first began reading, Shaykh Abdul Wahid al-Madani, one of the few remaining students of Shaykh Zakariyya Khandelwi, said he could not hear clearly, and I was told to move beside my husband, right by the grave. I felt shy, but I did not want to miss this opportunity, so I read in the clearest manner possible.

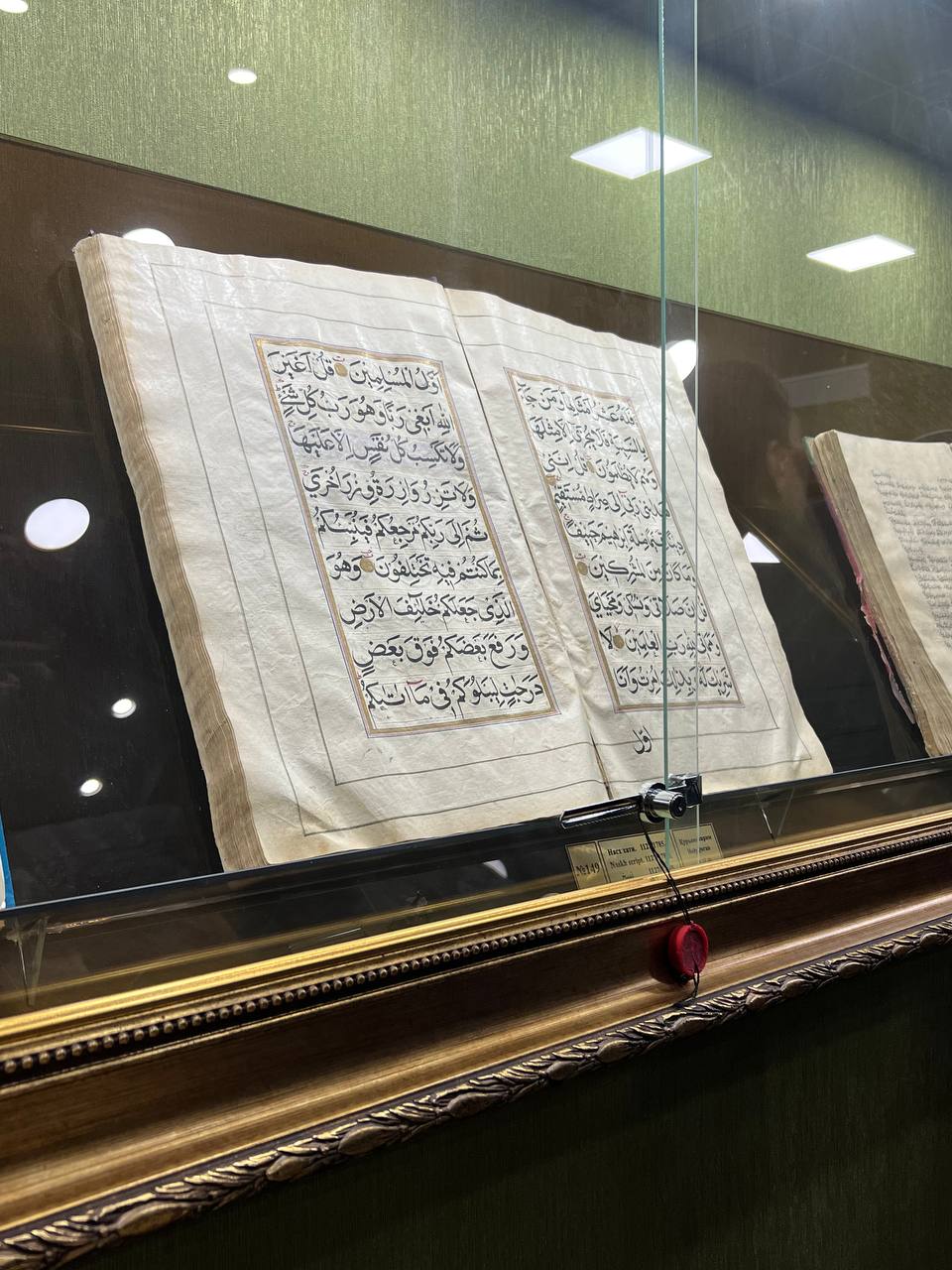

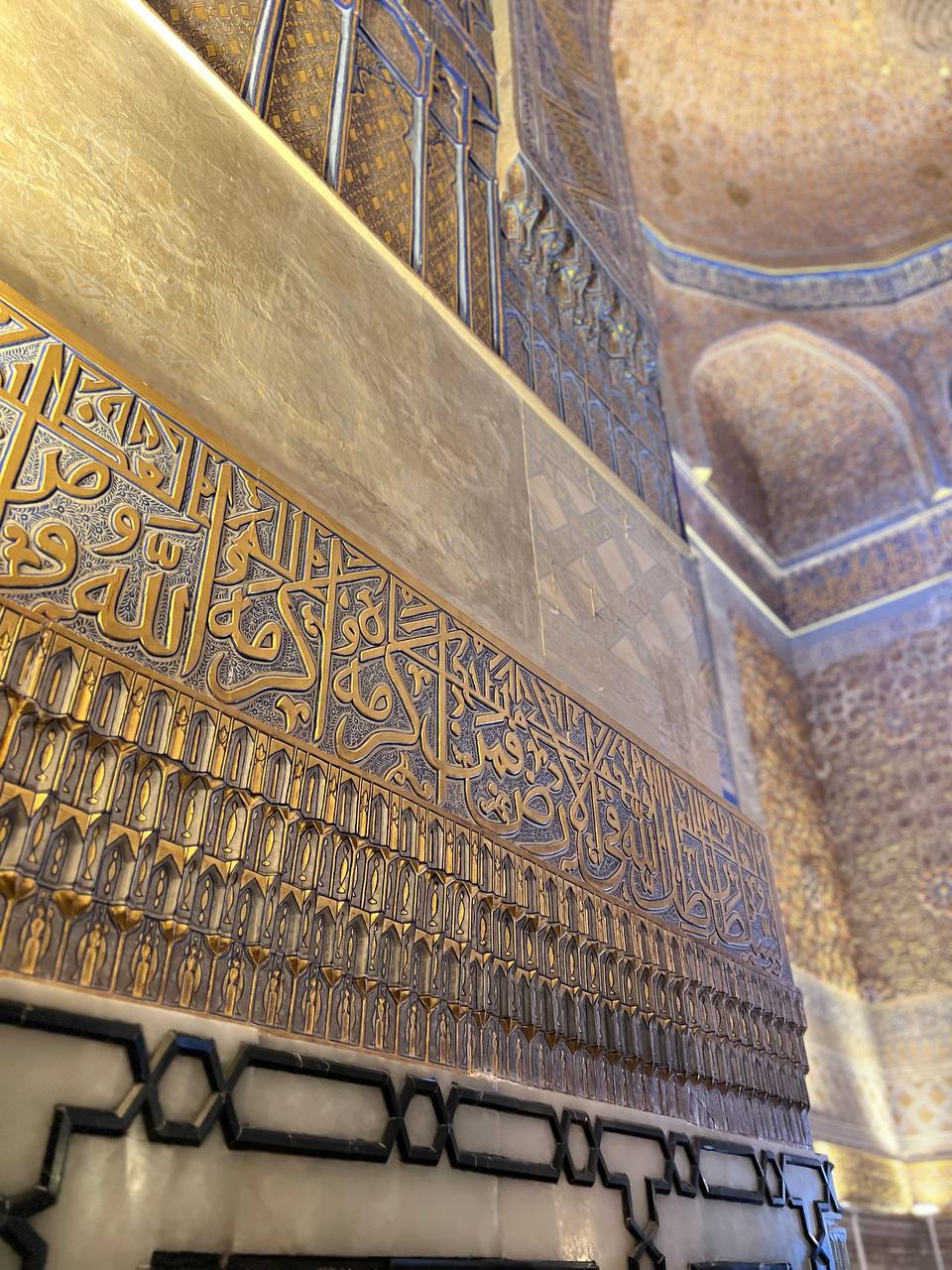

Following that, we entered the Mo’yi Muborak Madrasa building, which houses one of the four ancient copies of Muṣḥaf ʿUthmānī, which was written in Hijazi script on deer skin during the caliphate of ʿUthmān (raḍiy Allāhu ʿanh). This copy is considered one of the rarest manuscripts and was brought from Syria by Amir Temur in the 14th century. There were poles around the glass cover where the copy was placed with a sign that prohibited taking pictures. At some point during the 17th century CE, it was converted into a madrasa for students, but today, it serves as a library. It contains more than 20,000 manuscripts, lithographs of spiritual content, translations of the Qurʾān in more than 30 languages, and other books and manuscripts. What stood out for me was why this building was called ‘Mo’yi Muborak’. It is believed that a hair strand of the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) is buried in between one of the bricks in the building. However, the location of the hair strand has been kept hidden so that no one attempts to steal it for themselves. After this, we prayed in the Hazrati Imom Masjid, which had the most breathtaking interior.

Tashkent to Termiz

May 26, 2024 / Dhul Qa’da 18 1445

Early that morning, we had lessons on the Shama’il Sayyid al-Kawnayn (ﷺ) with Shaykh Mohammed Daniel & Shaykh Abdul Wahid al-Madani (may Allah preserve them), as well as 40 Ahadith on Daʿwa with Mufti Umayr ibn Zulfiqar.

Sultan Saodat Ensemble

We then flew one hour to Termiz and first visited the Sultan Saodat Ensemble, which is a collection of seventeen mausoleums that comprise the family burial place of the Termiz sayyids. It is said that they had to flee during the Abbasid dynasty in fear of persecution and ended up living and passing away here. The founder of the dynasty, Sayyid Ḥasan al-Emir, grandson and fifth in line from the Prophet Muḥammad (ﷺ), was buried here in the ninth century and set a precedent that his descendants were to follow for the next nine centuries.

This was a significant point to hear because my maternal grandfather, being from the same region, would always mention to his children that their family were sayyids. In fact, many of the difficulties he faced from the KGB and the Russia Regime was due him being sayyid. I wondered if my grandfather’s ancestors have any connection to this, and whether they were among those who fled persecution. After all, although this was about the Termiz Sayyids, there is historically little difference between these Eastern regions of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, it’s all Mā Warāʾ an-Naḥr. Moreover, my grandfather would say that his lineage goes back to Arabs, but Allah knows best.

Although I fully believe that my grandfather was a Sayyid, I don’t usually mention it to people. This article is the first time I’m sharing it. Unfortunately, many people falsely make this claim, so it’s understandable that people are sceptical. Furthermore, my grandfather had no official sanad (chain of authentication), which most people require to believe such claims. One reason I believe my grandfather’s claim is genuine is that he never used it to gain wealth or status. Instead, it was the main reason his family was targeted. It doesn’t make sense for someone in his position to claim something that could get him killed; it was simply who he was and he mentioned it to his children to remind them of the importance of holding on to Islam. Regardless, being a Sayyid does not guarantee Paradise or protect one from Hellfire, so we ask Allah to forgive him and raise his status.

Qirq-qiz Fortress

Next, we visited the Qirq-qiz (lit. Forty Girls) fortress, which was truly incredible. There are a few hypotheses by researchers about the function of this monument, although a famous one is that it functioned as a girls’ madrasa. It was built over 1200 years ago out of mud & straw and purposely had small windows to ensure privacy and modesty for the girls. It is said to be the first Islamic academy for girls, which is now preserved in a ruined state in the Termiz District.

Al-Hakim at-Tirmizi Mausoleum

Finally, we sat by the grave of Imam al-Ḥakīm at-Tirmidhī (d. 255 AH), a Persian jurist, traditionist, and author of Tasawwuf. Born and died in Mā Warāʾ an-Naḥr, he also travelled to Balkh, Nishapur, Baghdad, and performed Hajj around the age of 28. Among his many contributions to Hadith, Fiqh, Arabic, Anthropology, and Tasawwuf, he wrote an autobiography titled ‘Badʾu Shaʾn Abī ʿAbdillāh’. We read the introductions of seven of his works to gain ijāza. I had the honour of reading his Nawādir al-Uṣūl and Bayān al-Farq Bayn as-Ṣadr wa al-Qalb. This was a significant moment for me; it’s rare for a female student to read in front of shuyūkh and ṭalaba, often considered unnecessary or not legislated. I’m deeply grateful to Shaykh Mohammed Daniel for this opportunity. Though I haven’t studied with him long, he encourages and motivates female students just as much as male students.

Termiz to Shahrisabz

May 27, 2024 / Dhul Qa’da 18 1445

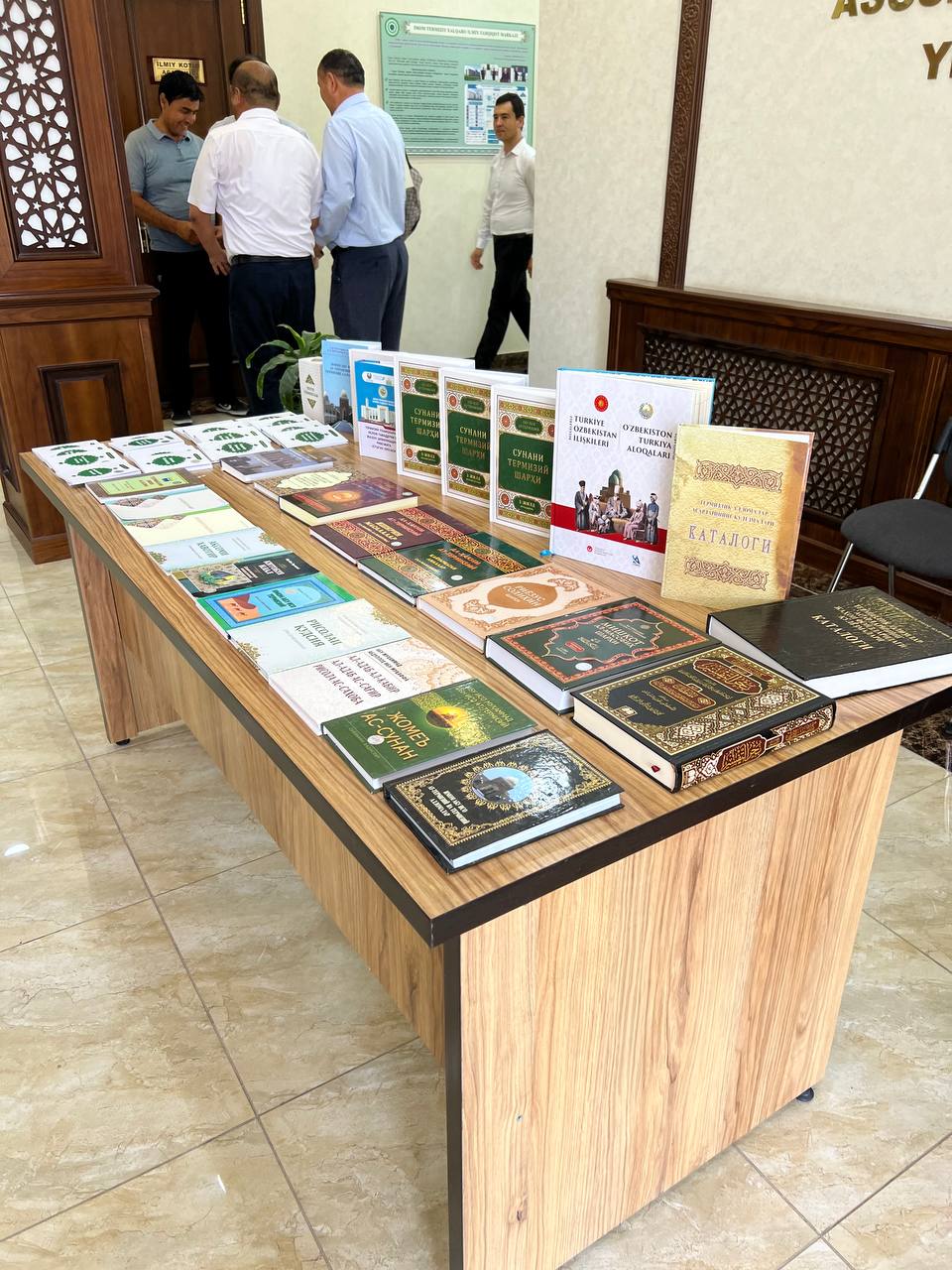

Imam Tirmizi Research Centre

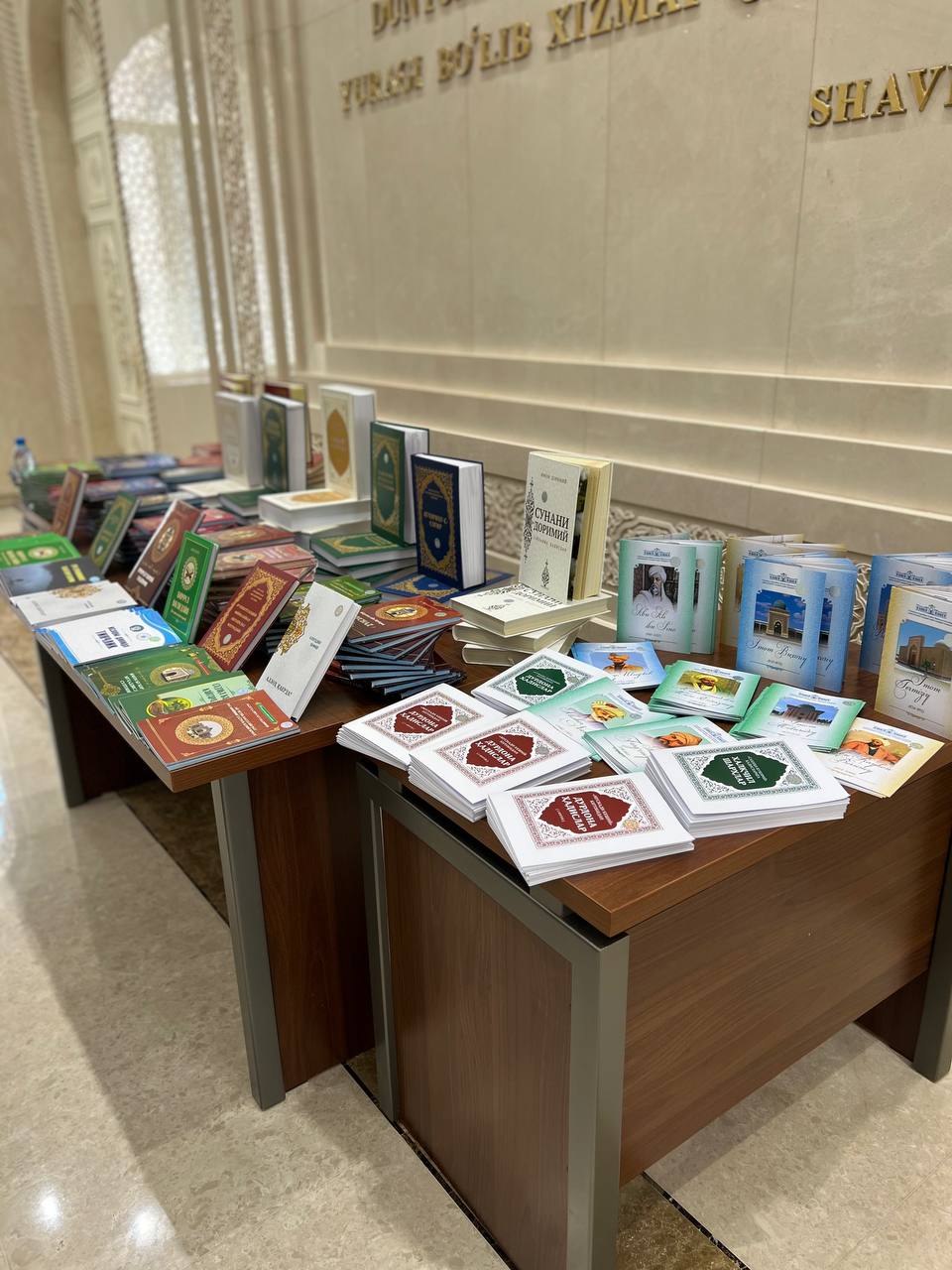

We spent the early morning in the Imam Tirmizi Research Centre. Here we listened to talks about Imam al-Ḥakīm at-Tirmidhī (different from the author of Jāmiʿ at-Tirmidhī), his works, as well as the efforts of the research centre in producing new works and translations. My husband read the beginning and end of Shama’il at-Tirmidhi, after which, written ijaza was granted to everyone who was present. I also met a recent graduate who had joined the research centre, Mukhlisa, whose specialty was Quranic Terminology.

Imam Tirmidhi Complex

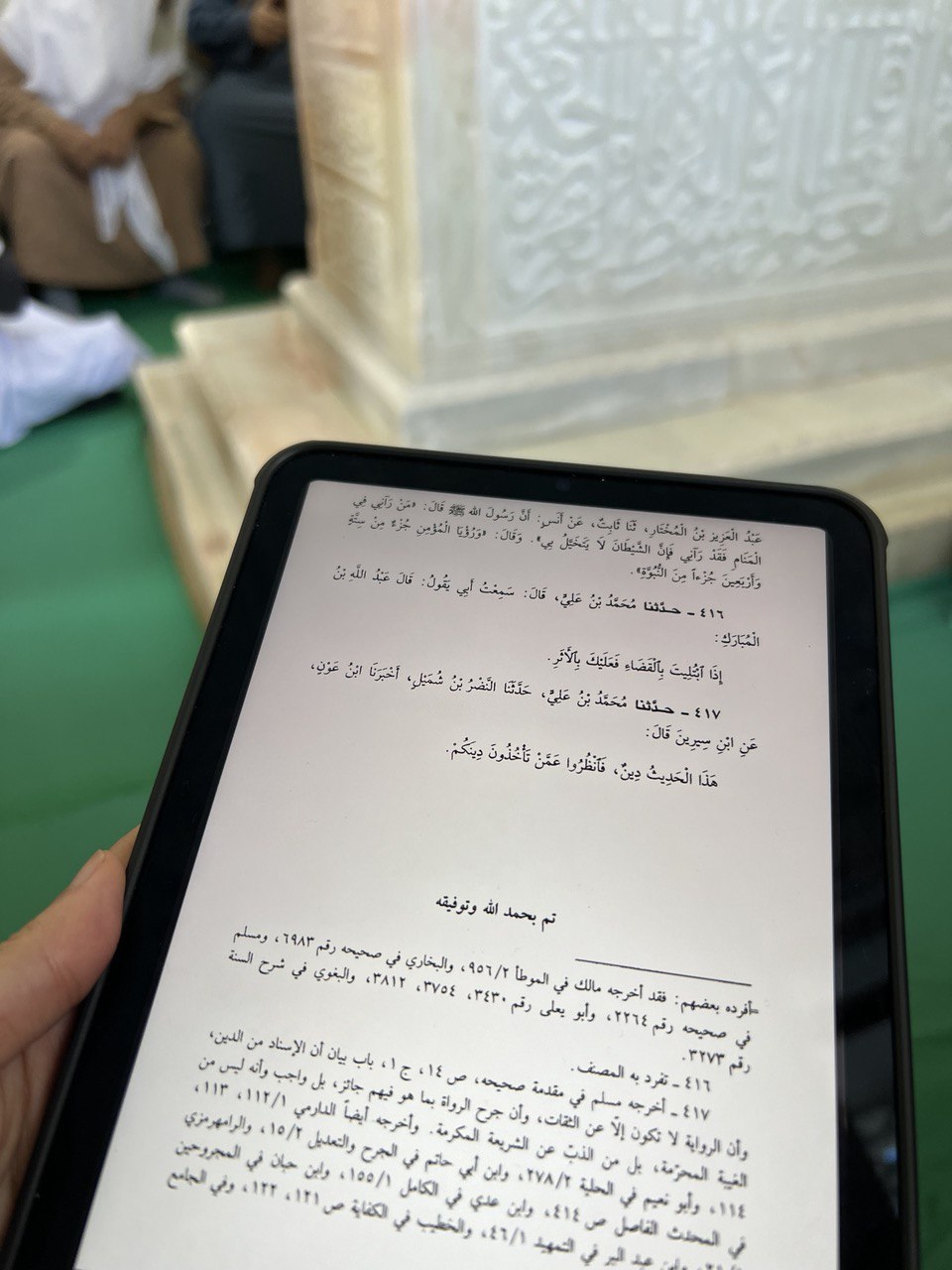

We then went to the Imam [Abū ʿĪsa] Tirmidhī Complex a little before noon and spent around 4 hours there. We started Imam Tirmidhī’s Shamāʾil by his grave, then stopped for Dhuhr and then continued until we finished. Prior to this, my husband and I had decided that we will divide the work—which consists of around 400 reports—between us. However, we visited the grave before even getting a chance to do so; hence, while I read a few chapters, he read most of the book. We both agreed that reading the whole of Imām Tirmidhī’s Shamāʾil by his grave was the most significant moment and a great blessing in our lives. For me, this was the most peaceful and touching moment.

I had so many feelings and thoughts. I felt so unworthy, yet so blessed. I kept having flashbacks to studying Jāmiʿ at-Tirmidhī and the Shamāʾil in 2016 with my honourable teacher, Mufti Ismail Kotwal (Allah preserve him), and now, I am reading the book by the grave of the Imam Tirmidhī? I reflected over ways I wanted to improve both my academic and spiritual life. Funnily enough, I also thought how this scene – if shared publicly – would quickly be interpreted by the ignorant to accuse us of things like grave worshipping, na’udhu billah. Yet, what we were doing was very far from that. None of us saw the deceased scholar as having the power to aid us in any way, and neither did we formally make du’a within that vicinity.

I was simply in awe of this Imam. “What an honorable life, and an honorable death,” I thought. As I sat there following my copy of Shamāʾil, I noticed a lady and her young daughter come in and sit in the space beside me. After scanning the room, seeing that we were reading something in Arabic, she took a mushaf, opened to a random spot, and just started to ‘follow along’. I could be wrong, but it seemed like she assumed that we were doing a Qurʾān khatm as Isal ath-Thawab and out of respect, wanted to join in. I could not help but conclude that she may not even know how to recite the Qurʾān, or may not be familiar enough to hear the difference between Qurʾānic verses and prophetic ahadith. Perhaps I was overthinking it, but I just felt so responsible at that moment.

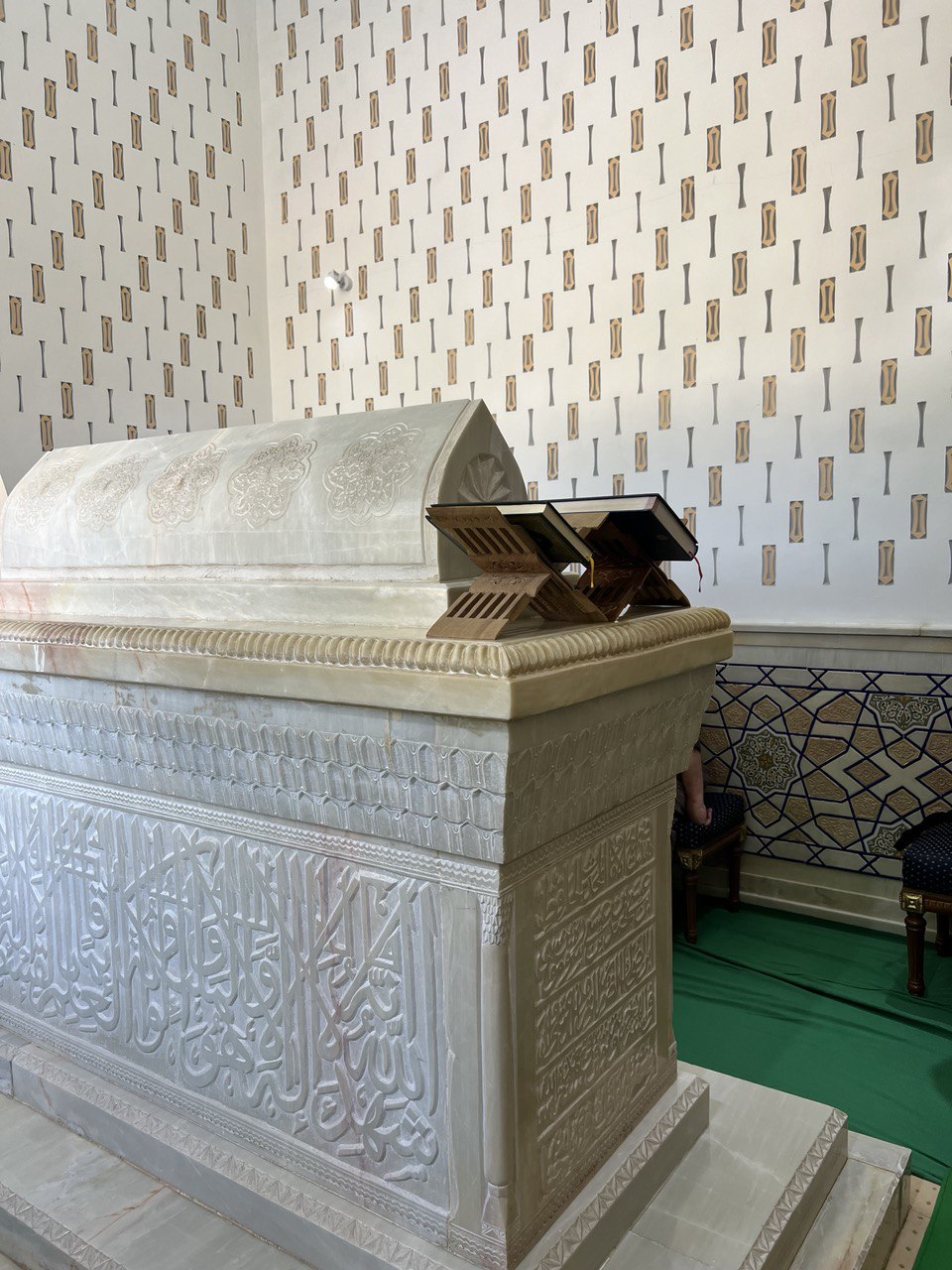

I also reflected on the beautiful and magnificent mausoleum built over Imam Tirmidhī’s grave. The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) instructed that graves should not be adorned or turned into monuments. So, how does the Government of Uzbekistan justify this? It’s true that they do it to honour scholars and saints, but what about the laypeople who might mistakenly believe that these deceased figures can grant them favours? At every gravesite we visited, I saw many women who would enter, sit, or make duʿā, then leave. Many of these women didn’t seem particularly religious, as they would only cover their hair and any exposed areas before entering. Although this was the case, interestingly, I did often see two types of signposts at the entrance of many complexes and mausoleums: one illustrating how both genders must dress modestly, and another prohibiting activities like grave worshipping, typing knots on trees, lighting lights, immodesty, etc.

After spending some time walking around the complex, we hit the road from Termiz to Shahrisabz by bus. I spent most of that bus ride reflecting. After completing my Islamic studies in 2016, I had a strong desire to go to Tajikistan and educate the population. It felt like the biggest priority. If I and a few other Persians didn’t make the sacrifice, who would? However, I knew it wasn’t possible for me.

After the fall of the USSR in 1991, Tajikistan, like Uzbekistan, gained independence and began to shed Soviet communist influence. I remember speaking to my family in 2010 via Skype, and seeing how religious they were becoming. My male relatives grew beards and attended the masjid, while my female relatives wore hijab. Unfortunately, with the rise of ISIL in 2011 and many Tajiks joining their ranks, President Emomali Rahmon – alayhi ma yastahiq – specifically banned practicing Islam. This forced me to abandon my dream of returning to Tajikistan to educate the women about Islam.

I struggled to find a new purpose where I was, which led me to the path of Hadith. However, after witnessing the progress in Uzbekistan, I felt my mission was possible again: “I could come and teach in Bukhara and Samarkand,” I thought. I prayed that Allah would allow me to return to these lands when I’m ready to teach and preach the Dīn of Allah. The people here have an intense thirst and appreciation for ‘ilm and dīn, but there are far too few preachers and scholars, especially female ones.

We soon reached our hotel in Shahrisabz and spent the night there.

Shahrisabz to Samarkand

May 28, 2024 / Dhul Qa’da 20 1445

Dorut Tilavat Complex

We started the day by visiting the Complex of Dorut Tilavat, which was also established by Amir Temur. This complex contains the tomb of Shamsuddin Kulol, Kok Gumbaz masjid, and the Blue Dome masjid. We then had a quick stop at the Aksaray fort, an architectural monument located in the city of Shahrisabz. The construction of this complex was started in 1380 by Amir Temur. We then headed to Samarkand.

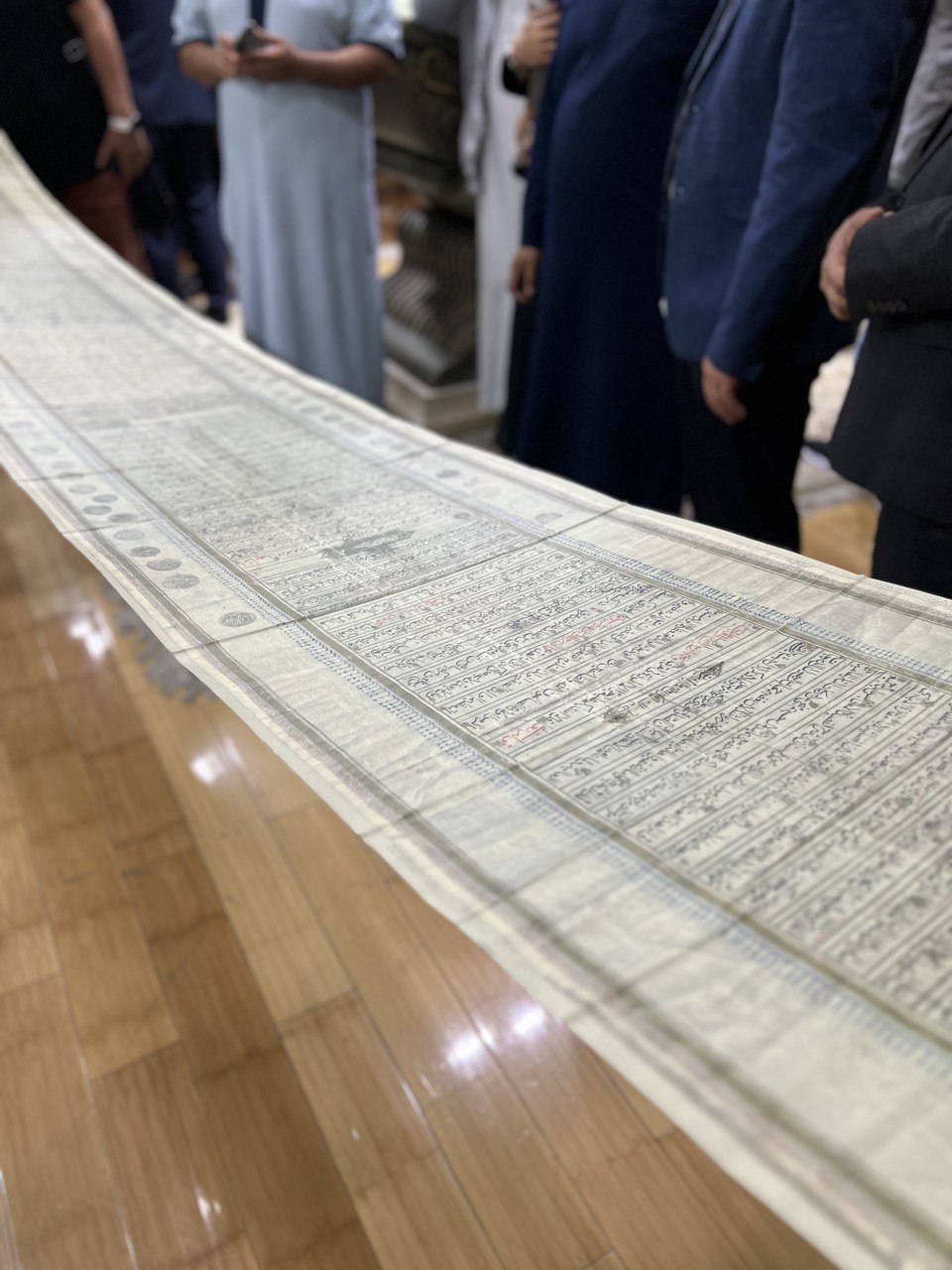

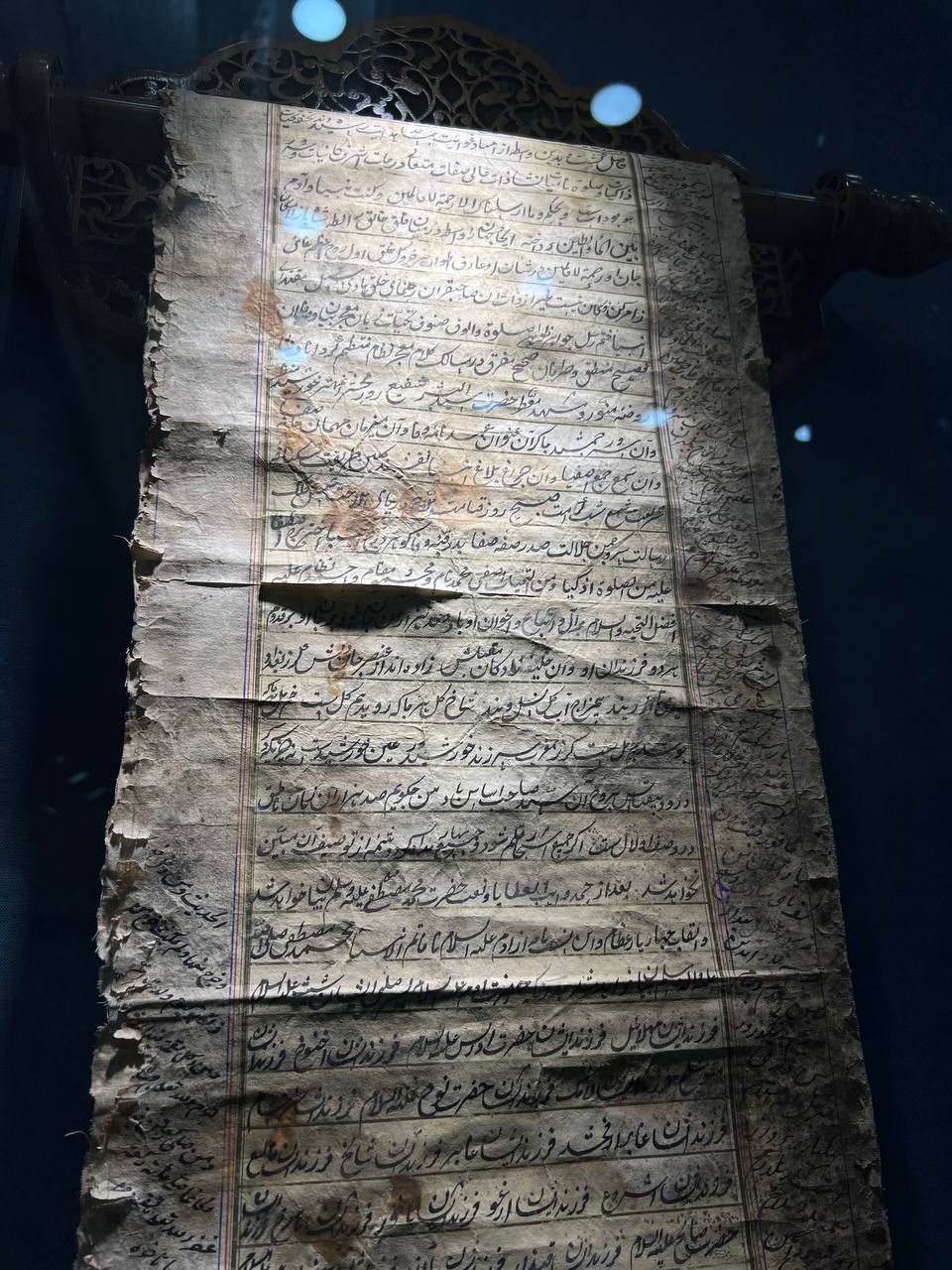

Imam Bukhari International Research Centre

We visited the Imam Bukhari International Research Centre, a project commissioned by the president himself. Its mission is to conduct deep research and widely disseminate the rich heritage of the Muslim world, highlighting their invaluable contributions to world civilization and science. The centre also aims to educate the younger generation about the true values of Islam. The centre housed old manuscripts of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and other significant works like ʿUmdat al-Qārī, the commentary of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. They also displayed books the centre had worked on and a long family genealogy scroll in Persian. As I looked closely at the scroll, I noticed the frequent repetition of the word “farzande,” which is the equivalent of “ibn” (son of) in Arabic. One of the most striking features was a huge wall painting depicting the famous event in Baghdad where scholars tested Imam Bukhari’s memory to verify his knowledge of hadith.

Imam al-Bukhari’s Grave

We then headed towards the grave of Imam al-Bukhari in Khartank. Unfortunately, we couldn’t get close since it was under construction. In a way, I was relieved. I felt too awed and shy to visit his grave. This gave me an excuse to return, and in the meantime, to improve my religious pursuits. May Allah allow us to visit his grave next time, and every time after that.

In the afternoon, we all sat by the mulberry trees to enjoy the sambusas Shaykh Daniel had ordered for us. While sitting on the grass, I noticed some kids playing on the mulberry trees and decided to speak Tajiki to them. We were in Samarkand, after all, where the Tajik population lives. Initially, I hesitated, thinking they might have grown up learning Uzbeki in school and not know Tajiki, but to my delight, they did.

We had a long, interesting conversation. They asked me about my niqāb (obviously!), and I asked them if they prayed namaz and practiced Islam. I tried to encourage them to practice their faith without being forceful. Knowing we had to leave soon, I pulled out my phone and took a short video with them. The girl’s name was Anora (meaning pomegranate-like), and she looked around 10 years old. The two boys were Paveez and Ali, who seemed to be around 9 and 8 years old.

Many people don’t know that Bukhara and Samarkand are culturally, historically, and linguistically Persian regions. They are not Uzbeki/Turkic. However, when the borders were created in 1991 after the fall of the USSR, these regions ended up in Uzbekistan rather than Tajikistan, where they naturally belong. Tajikistan is a Persian country that speaks Tajiki, one of three Persian dialects (along with Dari and Farsi).

Gūr-i Amīr

We then visited the Gūr-i Amīr, the mausoleum of the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur (also known as Tamerlane) in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Gūr-e Amīr means “Tomb of the King” in Persian. This architectural marvel, with its azure dome, houses the tombs of Tamerlane, his sons Shāh Rukh and Mīrān Shāh, and his grandsons Ulugh Beg and Muḥammad Sultan. Timur’s teacher, Sayyid Baraka, is also buried there.

Amir Timur, born in 1336, founded the Timurid Empire in and around modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia. As the first ruler of the Timurid dynasty, he led military campaigns across Western, South, and Central Asia, defeating powerful empires such as the Golden Horde, the Mamluks, and the late Delhi Sultanate. Timur is celebrated both as a brilliant military tactician and a patron of art and architecture. His empire laid the groundwork for the rise of lasting Islamic gunpowder empires in the 16th and 17th centuries. In Uzbekistan, he is revered as Amir Temur and is considered a national hero, as Central Asia flourished economically and culturally under his reign.

Personally, I have mixed feelings about him, and simply indifferent. While he made significant positive contributions, he also committed many evil acts. What bothered me most was that it seemed some people valued him more than the scholars buried in their lands.

Registan Square

Finally, we visited Registan Square. The Registan Square in Samarkand, Uzbekistan was the medieval heart of the city. It served as a public square where people gathered to hear royal news and witness justice being administered. Founded around 700 BC, Samarkand thrived as a prosperous centre of commerce along the Silk Road. The Registan, now part of the UNESCO World Heritage site, consists of three ornate madrasas adorned with glazed clay tiles. The Ulugh Beg Madrasa, dating back to 1420, is the oldest, while the Sher-Dor and Tillya-Kori madrasas were built in the 17th century. Today, the Registan remains a symbol of Samarkand’s prosperity and is beautifully illuminated at night.

Samarkand

May 30, 2024 / Dhul Qa’da 21 1445

Grave of Imam al-Maturidi

We started the day by visiting the grave of Imam Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī (d. 333 AH). Imam Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī was a prominent Sunni Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian. He is renowned for being the eponymous founder of the Maturidi school of Islamic theology. Born in Samarkand, he adhered to the Ḥanafī jurisprudence and codified a theological doctrine that refuted heterodox opinions. His tomb lies in the Chokardiza cemetery in Samarkand, where it is claimed that over 3,000 scholars and theologians are buried.

They said that chose to be buried in this area specifically because to his north is where the ṣaḥābī Quthum ibn ʿAbbās was buried, and to his south is the grave of Abū Muʿīzz ad-Dīn, a descendent of ʿUthmān (raḍiy Allāhu ʿanh). Around him are a number of tombstones that were found under a number of Jewish homes after the fall of the USSR. During the Soviet Union, many ethnic Jews of this area built their homes over graves and even used some of the tombstones as a part of their building material. They eventually found around 280 tombstones and have 20 of them displayed here.

Grave of Abū Layth as-Samarqandi

Then we headed to the grave of Imam Abū Layth as-Samarqandi (d. 375 AH), who was a Ḥanafī jurist who lived during the second half of the 10th century. Born in 944 in Samarkand, he authored several significant works, including the Quran exegesis known as Tafsīr as-Samarqandi and the treatise Tanbīh al-Ghāfilīn. We read the introduction to a few of his works, from among which, I read the Fatāwā an-Nawāzil and Mukhtalif ar-Riwāya.

Shah-i-Zinda Complex

We then headed to the Shāh-i-Zinda Complex. It includes mausoleums and other buildings spanning from the 11th to the 19th centuries. The name “Shah-i-Zinda” means “The Living King” and is connected to the fact that Qutham ibn Abbas (raḍiy Allāhu ʿanh), a cousin of Muhammad (ﷺ), is buried here. The complex features more than twenty buildings, with structures dating back to different periods. Other notable elements include the Khoja-Ahmad Mausoleum, and the Turkan Ago Mausoleum.

Qutham ibn ʿAbbās was the ṣaḥābī who was ordered by Saʿīd Ibn ʿUthmān to remain in Samarkand and propagate Islam. In 677, Samarkand was attacked by Sogdians, and Qutham ibn Abbas died defending the city. During the reign of Amir Temur, a mausoleum for Qutham ibn ʿAbbās was constructed at his grave.

Abdulkholiq Ghijduvani Complex

Then we headed to Bukhara, and on our way, we stopped by the Abdukholiq Ghijduvani Complex, where we visited the Abdukholiq Ghijduvani grave and the Ulugbek madrasa. Here, Imam Ghijduvani is buried by the feet of his mother, because he wanted to physically practice upon the hadith: “paradise is under the feet of mothers.”

Bukhara

May 31, 2024 / Dhul Qa’da 22 1445

Grave of Amir Kulol

After arriving in Bukhara and resting the night, we started the day by visiting the grave of Amir Kulol (d. 1378 AH), the teacher of Bahāʾ ad-Dīn an-Naqshbandī. Amir Kulāl, born Shams ud-Dīn in 1278, was a Persian Sufi Islamic scholar and a member of the mystical Khajagan order. His father, Amir Saif ud-Dīn Hamza, was a Sayyid descendant of Muḥammad and the chieftain of the Persian Kulal tribe.

Then, we headed to a nearby restaurant for lunch to eat the traditional rice dish known as ‘plov‘ in Russian or ‘osh‘ in Tajiki. It is very similar to the Afghani qabili palaw but we use bigger rice grains similar to ricotta rice, cut the carrots in shorter pieces, and cube the meat. Most importantly, we use flaxseed oil which makes it taste very different.

Bazar in Bukhara

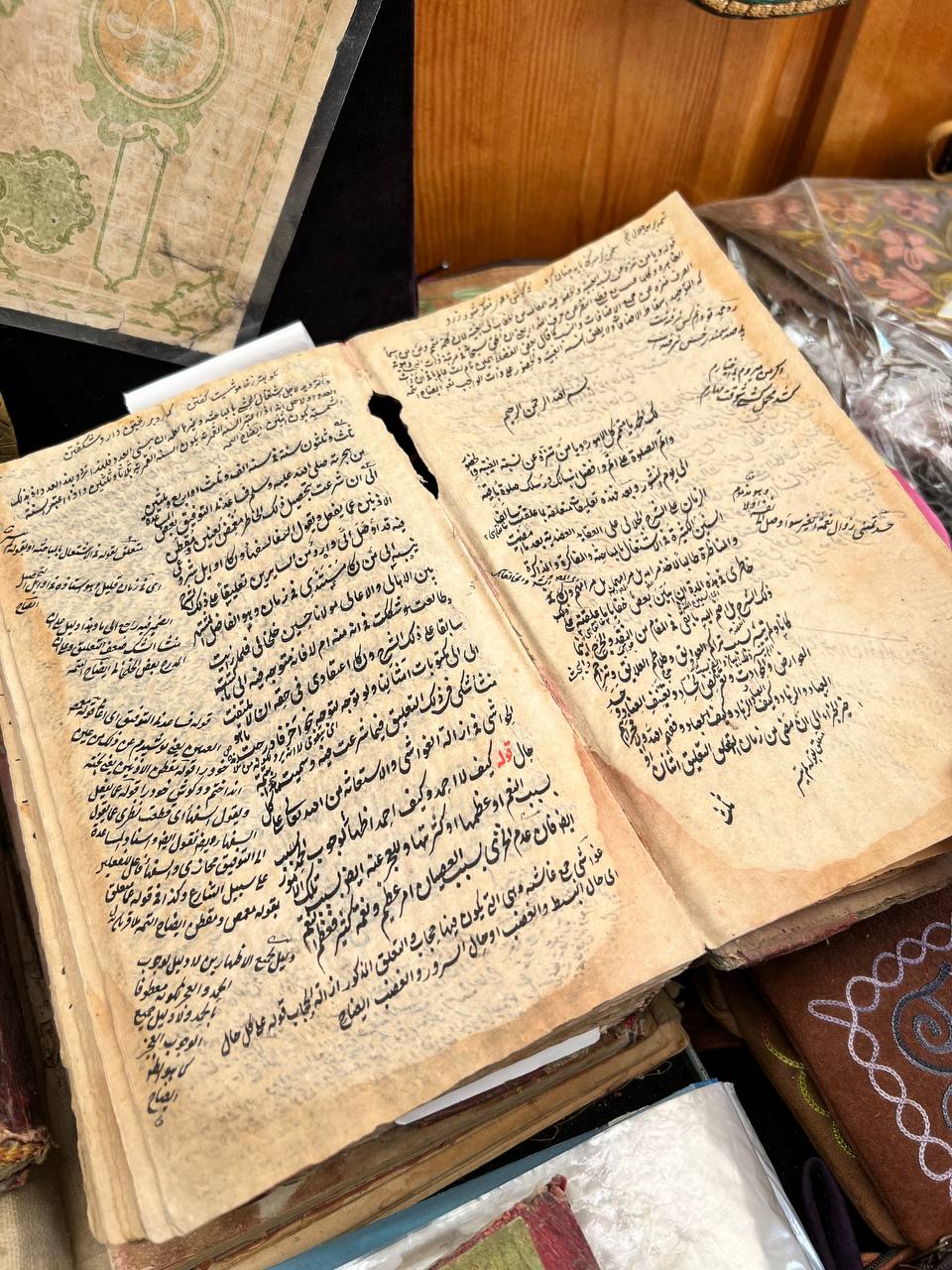

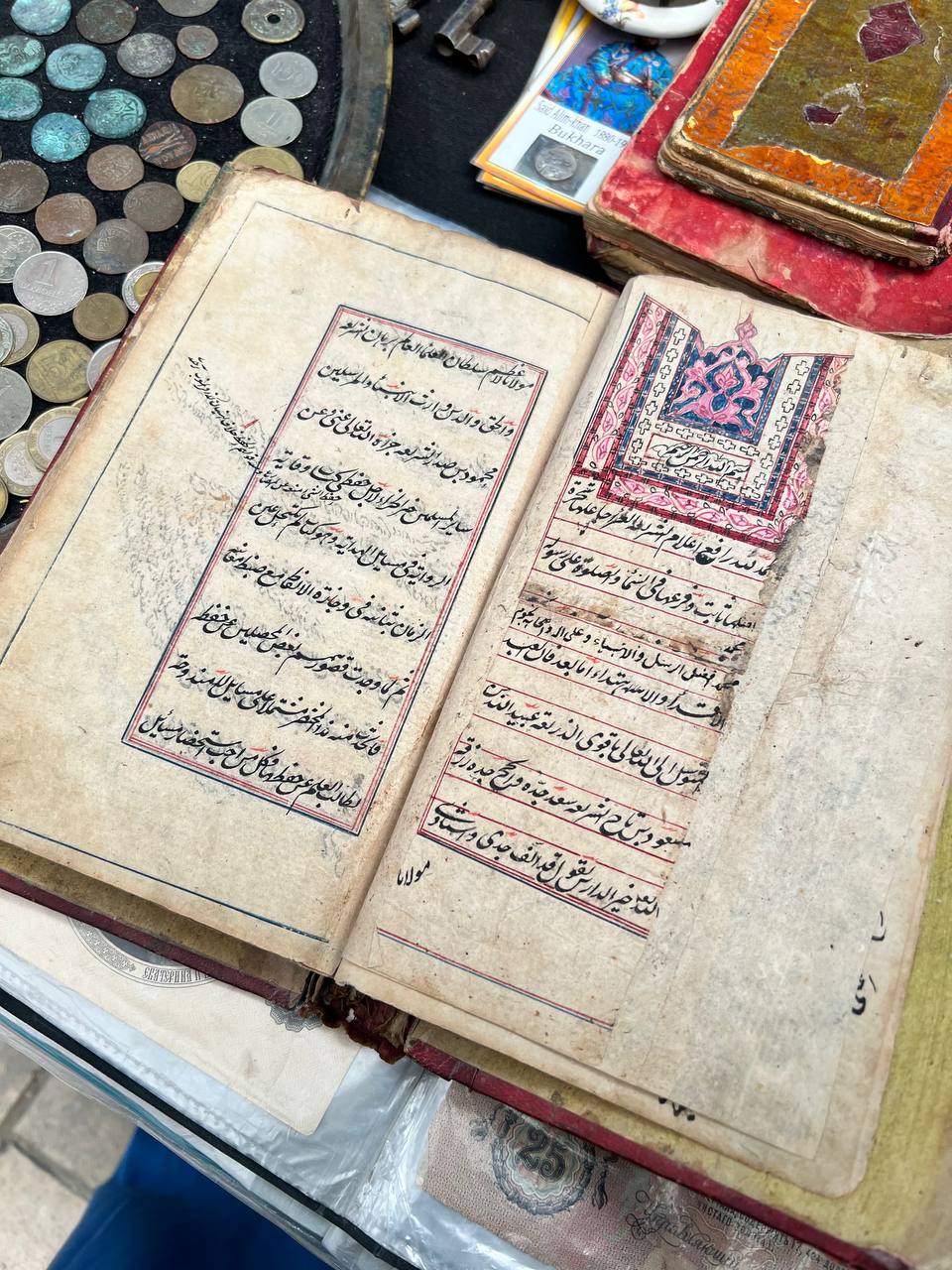

We then went to the Bazaar in Bukhara, where I had the chance to buy some gifts and adras dresses for my mother and sisters. While passing a typical souvenir stall, my eyes fell on what looked like old manuscripts. I opened them and was surprised and impressed to find that these were indeed old manuscripts, casually for sale in a souvenir shop. One was an old Qurʾān manuscript, another was a fiqh manuscript, and another was Persian poetry. My husband noticed them too and we wondered if one might be extremely valuable and worth publishing. He asked for their prices, which ranged from $200 to $800. The price wasn’t the issue, though; it was the legality. Taking manuscripts over 50 years old out of the country is illegal. That was unfortunate, but khayr.

Feeling tired, I sat by the silk carpet shop where everyone was browsing. While I sat, an orange cat—whose tail had been slightly but constantly tugged by a little girl earlier—slowly made its way into my lap. It seemed less than a year old and reminded me of my fluffy white Ragdoll named ‘Shayba’ back in Canada.

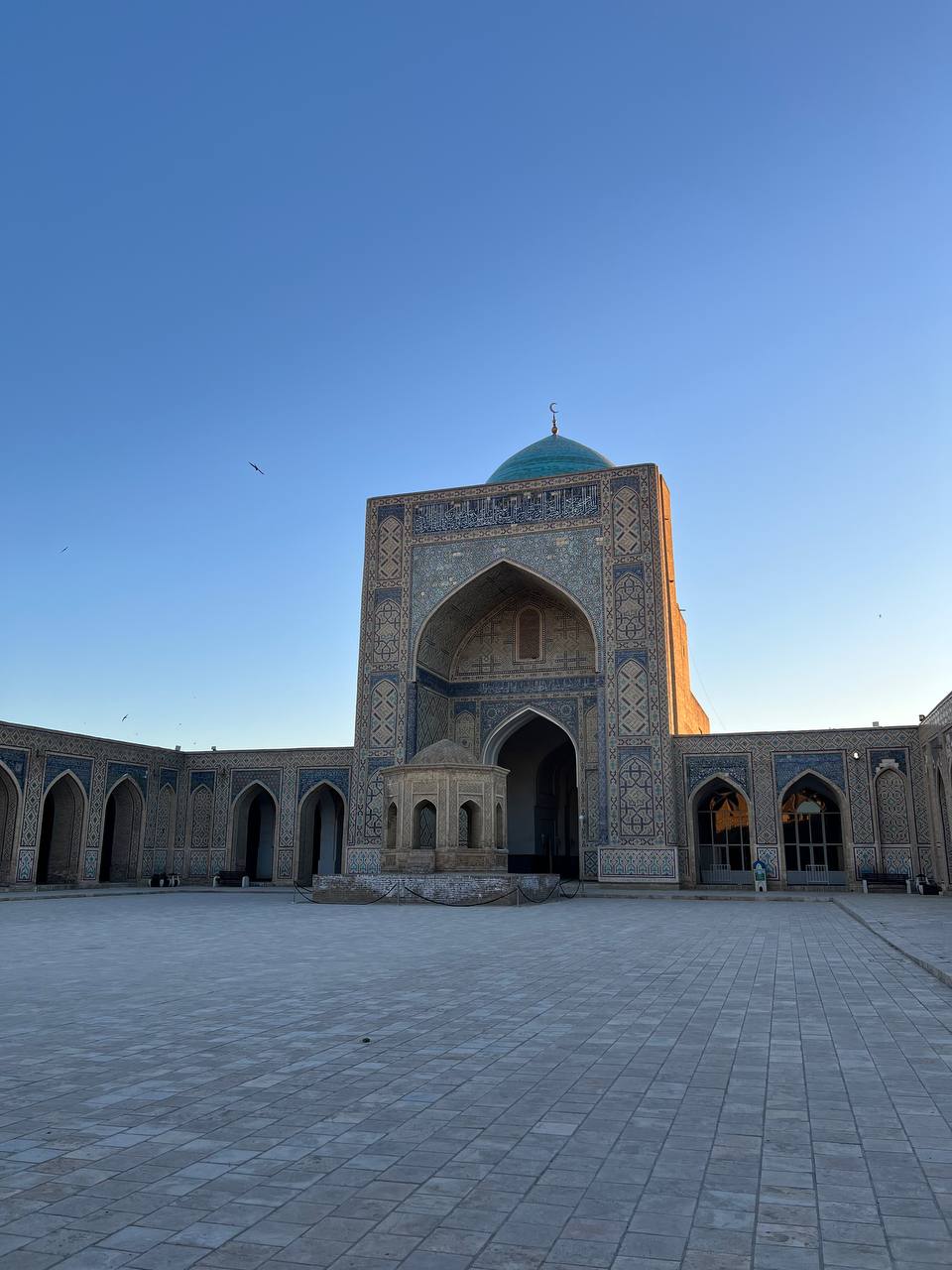

Poi Kalon Ensemble

By now it was late afternoon and we headed towards the Poi Kalom ensemble, where we visited the Mir-i-Arab madrasa and Kalon masjid. The Poi Kalon ensemble consists of three buildings built in the 12th-16th centuries: Miri Arab Madrasa, Kalon (lit. big or high) Masjid, and Minaret Kalon.

In 1127, the Kalon Minaret with a height of 46.5 meters was erected by the order of the Karakhanid king Arslan-Khan. Inside the minaret, there is a spiral staircase with more than one hundred steps. In 1514, by the order of Ubaydullah Khan, on the place of the destroyed Karakhanid Masjid was built, the second largest (after Bibi-Khanum Masjid in Samarkand) masjidof the country—Kalon Masjid. The masjid has a rectangular plan, with a spacious inner courtyard and accommodates more than 10,000 people in the congregation at the same time.

In 1535-1536, Ubaydullah Khan invested heavily in constructing the Miri-Arab Madrasa for Shaykh Abdullah of Yemen, an influential spiritual mentor of the ruler. The Miri-Arab Madrasa has been continuously used for its intended purpose as a centre for learning the Islamic religion. This madrasa was quite similar to the one in Tashkent, but it was in Bukhara, and many of the students looked more Persian than Turkic.

As I walked slowly around, I noticed a few youngsters sitting in the courtyard, seemingly memorizing hadith. I quietly passed behind one and listened carefully, hearing him recite the hadith of ‘al-muslimu man salima.’ This made me think he might be memorising the Arbaʿīn of Imam Nawawī. Although this was a boys-only madrasa, I felt so grateful to witness this. This is just the beginning, and insha’Allah, in the coming decades, Islamic learning centres will truly flourish.

I felt reassured seeing my people studying Islam, working towards reviving what was lost during the Soviet regime. I spotted my husband speaking to one of the students in Arabic and went to stand behind him to listen. They talked about various topics—the yaktaks, the curriculum, and more. At one point, my husband jokingly told the student, “You need to grow your beard more,” to which the student replied, “Unfortunately, they don’t allow us to grow it more than this.”

I wasn’t shocked because, after all, it’s only been roughly two decades since independence, eight years since Shavkat Mirziyoyev became the new president, and three years since the ban on hijab was lifted. This doesn’t mean there is now total freedom and no control. Given what happened with ISIL, things will not change overnight. The president wants to reintroduce everything gradually and ensure that people are properly educated.

Bukhara

June 1, 2024 / Dhul Qa’da 23 1445

Abu Hafs Memorial Complex

After spending another night in Bukhara, we visited the grave of Abū Ḥafṣ al-Kabīr, Abū Ḥafṣ aṣ-Ṣaghīr, and ʿAbdullāh ibn Muḥammad Yaʿqūb al-Ḥārithī in the Abū Ḥafṣ Kabīr Bukhārī Memorial Complex. The mausoleum was built in the 9th century but later demolished during Soviet rule. It was reconstructed in 2009–2010. We sat by their graves, and this is where I read the section of Musalsal bi al-Fuqahāʾ al-Ḥanafiyya from al-Faḍl al-Mubīn.

Baland Masjid

Thereafter, we visited the Baland Masjid. It was built in the 16th century and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its intricate architecture includes a dual-purpose prayer room for both winter and summer. The winter room features frescoes, mosaics, and gilded floral themes, while the summer prayer room has wooden muqarnas decor.

Train to Tashkent

We soon headed to the train station to head back four hours to Tashkent. I took the opportunity to directly read the Thulāthiyyāt al-Aʾimma to Shaykha Fāten Umm Ibrāhīm ad-Dimashqiyya after which, she issued me a handwritten ijāza. I really wanted to hear all her rihla stories, but most of the time knowing how tiring the journey can be, I chose to leave her to rest. I hope to see her more often, for after all, she was the only musnida I have come across. After returning to my seat, and doing a little bit of reading, I can’t say much else. I fell asleep. After reaching the Daniel Hills hotel back in Tashkent, we had our final classes and did our final reading of a few books, after which we were issued our ijāzas for the books that we read throughout the retreat. Some people were leaving the next morning, although we and a few other people planned to join Shaykh Daniel and his family to the mountainside the next day.

We left after a few more days. This journey through Uzbekistan was more than a trip; it reconnected me with my heritage and strengthened my commitment to Islamic scholarship. The history, scholars’ graves, and vibrant culture deeply impressed me. May Allah help us continue seeking knowledge and serving His Dīn.

My Grandfather, May Allah have Mercy on Him

I have always been captivated by the story of my maternal grandfather, Ziyarat Shah Mir Sayyid. He was born on May 5, 1911, and grew up in Dara-i-Vang, in the Gorno-Badakhshan district of Tajikistan, during a time of great turmoil. His life unfolded during the Soviet Regime, a period marked by communism and harsh religious persecution. His father, Mir Sayyid, and his older brother were known as ‘Mullas,’ and in 1925, his father sent him to Samarkand to study Islam. Unfortunately, this journey was cut short by the oppressive Soviet KGB, which sought to eradicate religious figures and practices.

I often wonder if the whole reason I got to study Islam and eventually start teaching it, is because of some du’a that my grandfather made? Yet he passed away around 1991 not knowing how his du’a eventually got accepted. How beautiful is the work of Allah? My mother was his 12th and final child, and when he passed away, she was only 18, so my grandfather never even got to know of me. In this is a lesson for us; your du’a may get accepted in the most appropriate time, yet you may not be there to witness is. Such is the beauty of tawakkul.

When my grandfather returned to Tajikistan, he was met with devastating news: his father had passed away, and his brother had been murdered, likely by the KGB. The regime targeted those who appeared religious or were sayyids, pressuring them to adopt teaching positions of the new Cyrillic script as a means of showing their loyalty to the new regime. Tajiki, a dialect of Persian, was originally written in the Farsi script. After becoming a teacher, my grandfather was sent to Vahdat, Dushanbe, where he would eventually meet my Tatar grandmother.

In 1938, he was called to train for World War II and eventually ended up in a Nazi concentration camp. He recounted to my mother how, when the Russians finally liberated the hostages, they weighed everyone and took pictures as a way of tracking their recovery. At that time, he weighed only 42 kg! Even after the war ended in 1945, he was held back to assist with Japan’s borders and later to help rebuild Saint Petersburg.

Finally, around 1948, he returned home and got married. Practicing Islam under the Soviet regime was fraught with difficulty. People were banned from attending masjids, wearing scarves, praying salah, fasting or even owning a copy of the Qur’an. Masjids were repurposed as community centres called ‘clubs.’ My mother remembers the Jame’ masjid in our village being used as a cinema, showing Bollywood movies every week or two. “A car carrying tickets to the latest Bollywood movie would drive by honking, and everyone would be jumping in excitement” my mother told me. This environment of misguidance, delusion, mindless entertainment, and the oppressive grip of Soviet enslavement is what my grandfather was forced to raise his children in. He would pray salah in secret, and he and my grandmother would discreetly eat suhur, using a small lamp and eating leftovers from dinner stored in the ‘sandali‘ (a heater made by placing hot coal under a short table and covering it with a blanket).

Most nights, my grandfather would quietly teach my mother and her siblings the basics of Islam. Though he wasn’t a scholar, he shared what he knew with passion and sincerity.

“Hear me, our Lord is One.”

“The azab of the qabr is haqq, my children.”

“There are eight doors of Jannah, and seven levels of Jahannum”

“The pillars of Islam are five…”

“A horseshoe and blue eye bead cannot help you in anyway”

“Keep these beliefs in your hearts, but don’t speak of them to outsiders.”

He was careful not to instruct them to wear a scarf or pray openly, knowing it could lead to persecution.

He had dug a hole in the wall of his home to hide his mushaf and other Islamic books, covering them with a layer of mud. Once, while rebuilding a friend’s home, he found more books hidden within the walls and kept those too. In his later years, my grandmother visited Russia and brought back a copy of the Qur’an. When my grandfather opened it, he wept, realising how long it had been since he had held a mushaf and how his reading ability had weakened. However, with practice, he soon regained his reading skills and would often read the Qur’an after that. By then, he was old, and the Soviet Regime largely ignored elderly people practicing their faith, as long as they kept to themselves.

The Soviet Regime had officially changed his last name from ‘Mir Sayyid’ to ‘Saidov.’ My mother explained that the Soviets altered names that were overtly Islamic. For instance, ‘Abdul Rahman’ became ‘Rahmanov’ or ‘Rahmanova’ for women, and ‘Abdul Rahim’ became ‘Rahimov’ or ‘Rahimova.’ Thus, although my mother’s last name should have been Saidzada (meaning ‘The Sayyid Family’), it was changed to ‘Saidova.’ Mine was also Saidova for a long time until I reverted it to ‘Saidzada.’

May Allah have mercy on the scholars of Mā Warāʾ an-Naḥr. May Allah allow Islam to prosper in these lands and make them centres of learning once again. May Allah forgive my grandfather Ziyarat Shah Mir Sayyid and allow us to unite in Jannah, amin.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to comment them below.

Such a beautiful rihla ✨. Uzbekistan has been a dream for me too. As a student of knowledge I pray I am granted the opportunity to go on Jamaat there. Your post was very inspiring and informative. Jazakillah Khairal jazaa and may He fulfill your aspirations. 🫶🏾

LikeLike

Jazākillāhu Khairan for sharing! You’ve penned it down beautifully, māshā Allāh – felt like I was on a virtual tour of this beautiful city, the dream of every student of hadīth. The rich history and cultural heritage of Uzbekistan definitely came alive through your words.

May Allāh accept you as a revival of the sciences of Hadīth, especially amongst females, in the lands of the great Muhaddithun. p.s. 100% agreed with what you mentioned regarding cultural modest dress!

LikeLiked by 1 person